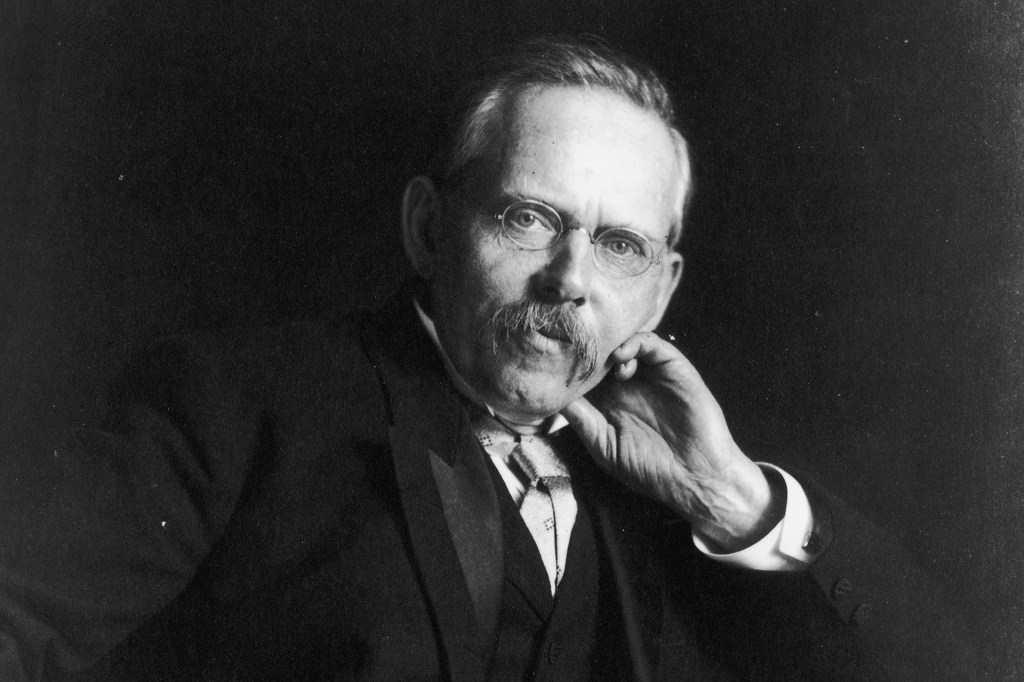

Jacob Riis

Jacob Riis (May 3, 1849—May 26, 1914) was a photojournalist who documented the lives of poor New Yorkers in the 1890s. He published the photographs in his book How the Other Half Lives. The pictures shocked Americans and inspired a wave of social reform.

Jacob August Riis was 21 years old when he boarded the S.S. Iowa in Glasgow, Scotland. He was headed for New York City. He carried $40 in his pocket and not much else. Riis struggled to find a job once he arrived in the United States. His experiences living in some of New York’s poorest neighborhoods helped him become one of the most influential photojournalists in American history.

After arriving in New York, Riis held a variety of odd jobs. He worked as a farmhand, bricklayer, carpenter, and salesman. After being homeless for some time, he landed a job as a reporter for the New York News Association. He later became the editor of the South Brooklyn News, a small community newspaper. In 1877, he joined the New York Tribune as a police reporter. He covered some of the city’s most dangerous areas. Riis, who had lived in low-rent tenement buildings, was familiar with the difficult conditions that immigrants faced on a daily basis. As a journalist for the Tribune, he wrote about the realities of immigrant neighborhoods.

While working as a police reporter, Riis developed a close friendship with New York police commissioner—and future U.S. president—Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt admired Riis’s work. He believed Riis possessed “the great gift of making others see what he saw and feel what he felt.” In order to show his readers see what he saw, Riis bought a wooden box camera and taught himself how to use it.

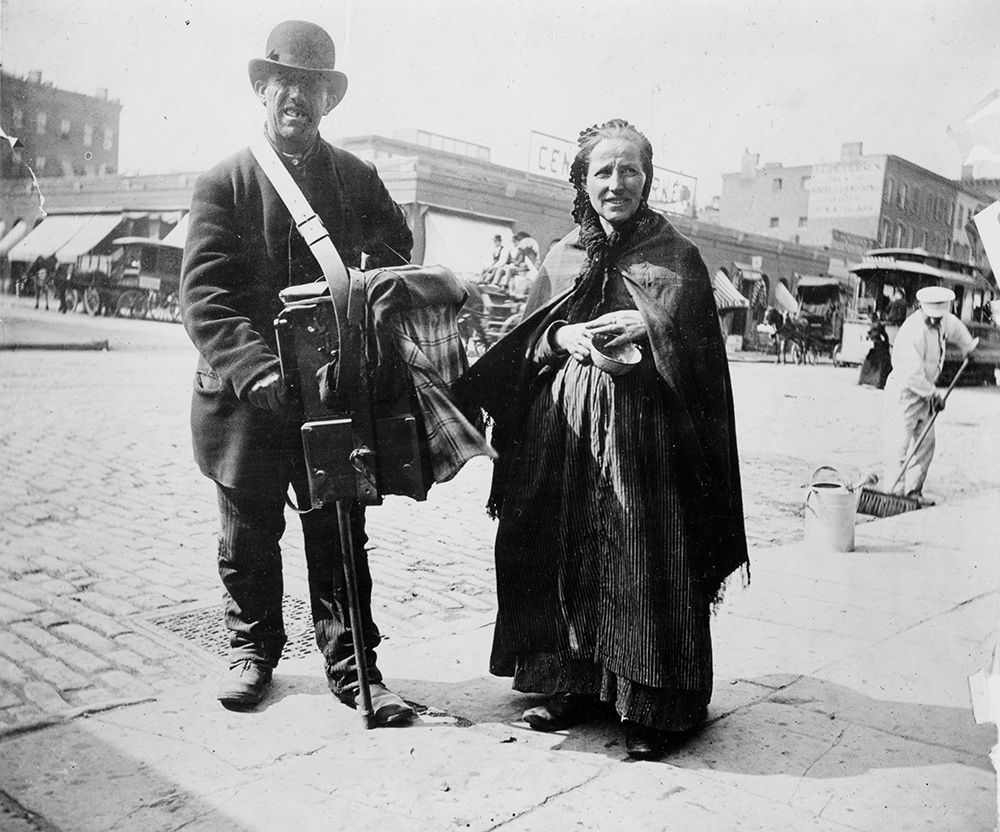

At the time, photographers were just beginning to use a flash to light their pictures. It relied on explosives to illuminate a scene. Riis saw this new technology as a way to capture tenement life. While the process was important for Riis’s reporting, it was also dangerous. Riis reportedly set two fires and almost blinded himself while using a flash.

Riis focused on photographing immigrants, street dwellers, and tenement buildings in New York City. Here, he captures a musician as his wife holds a tin cup for donations.

JACOB RIIS—PHOTO-QUEST/GETTY IMAGESHow the Other Half Lives

During the 19th century, New York City saw a fast increase in population. Immigrants from Europe and Asia were looking for a new life in the U.S. Most were escaping war and famine. The newly arrived groups gathered in hardscrabble neighborhoods like the Lower East Side of Manhattan. They loaded into single-family homes that had been transformed into multiple-apartment buildings. By 1900, two-thirds of the city’s population lived in overcrowded tenement buildings. Conditions were unsafe and unsanitary. Most lacked indoor plumbing. Often, rooms facing the street were the only ones to get light and air. Back rooms had no ventilation at all. This helped the spread of diseases like typhus. Those who could not afford to live in tenements would often sleep on the streets, in alleyways, or in parks.

In 1888, Riis left the New York Tribune for a job at the Evening Sun. There, he continued documenting the harsh living conditions of the poor. In 1890, he published his first book, How the Other Half Lives. In the introduction, he wrote, “Long ago it was said that ‘one half of the world does not know how the other half lives.’ That was true then. It did not know because it did not care.” The monumental book included photographs Riis had taken throughout the city. Yet what set it apart were the solutions Riis suggested to many of the city’s problems. “The whole matter resolves itself once more into a question of education,” he wrote.

Time for Progress

The impact of How the Other Half Lives was immediately felt. For the first time, readers saw photos of New York City’s neediest people and poorest areas. With his book, Riis helped launch the Progressive Era. Progressives, like Riis, aimed to address social and economic problems caused by industrialization in urban communities. Riis believed that poverty was a result of environmental conditions. He also believed that government played a big part in making it better or worse.

Riis called for proper lighting and sanitation in the city’s lower-class housing. He asked citizens from the upper and middle classes to take an active role in shaping their neighborhoods by helping those less fortunate. Inspired by these suggestions, police commissioner Roosevelt closed the more dangerous tenements. He also promoted legislation to improve living conditions for immigrant communities.

With Riis’s help, the New York City Board of Health cleaned up the city’s tenements. In 1901, a Lower East Side settlement house on Henry Street was renamed the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement House. It provided housing as well as recreational and educational resources for New York’s poorest residents. Today, Riis Settlement provides resources for underserved communities in Queens, New York.

Riis died on May 26, 1914. In a telegram, President Roosevelt called Riis “the most useful New Yorker.” He added, “In all the United States, I never knew a more useful man nor a stauncher citizen.”