KAKUMA, Kenya — Wild animals roamed at night, but Rose Peter and the 19 other children she was with still managed to sleep in the bush. In daylight, they walked. “One week,” Rose tells me when I ask how long the trip took. She says they set off alone from South Sudan to Kenya. (Their parents came later.) Aid workers picked them up at the border and drove them two hours south to Kakuma refugee camp. That was in 2014. Rose has lived here ever since.

HOME AWAY FROM HOME Kakuma camp (pictured) and Kalobeyei settlement are home to nearly 186,000 refugees from 19 countries.

JOERG BOETHLING—ALAMY PHOTO STOCK. MAPS BY JOE LEMONNIER FOR TIME FOR KIDS“There was a war in my country,” Rose says through a translator. In fact, civil war still rages in South Sudan. We are standing outside in the hot sun in a dusty compound of mud-walled homes. “I am hoping that after I finish school, my life will be changed completely,” Rose says.

Rose, 18, is a refugee. A refugee is a person who has fled his or her country due to war or fear of persecution

persecution

MICHAEL GOTTSCHALK/GETTY

treatment that is unfair or cruel, especially due to someone's race, religion, or political beliefs

(noun)

Malala Yousafzai fled persecution in her home country of Pakistan.

because of race, religion, or nationality. Political opinion or membership in certain social groups can also play a role. A United Nations agreement called the 1951 Refugee Convention formally defines the term refugee. It also lays out refugees’ rights. These include the right to food, shelter, and, for children, education.

MICHAEL GOTTSCHALK/GETTY

treatment that is unfair or cruel, especially due to someone's race, religion, or political beliefs

(noun)

Malala Yousafzai fled persecution in her home country of Pakistan.

because of race, religion, or nationality. Political opinion or membership in certain social groups can also play a role. A United Nations agreement called the 1951 Refugee Convention formally defines the term refugee. It also lays out refugees’ rights. These include the right to food, shelter, and, for children, education.

In March, I traveled to Kakuma with UNICEF, the United Nations Children's Fund, to learn what it’s like for refugee kids to live and go to school there. At the Kakuma Reception Center, where refugees stay when they first arrive, I met 15-year-old Jackson, who’d come from South Sudan without family. At a community garden, Alice, 11, showed off a plot of bean plants emerging from the soil. And at the Furaha Center playground, children called out in delight while being pushed on swings by caring adults. In Kenya’s Kiswahili language, furaha means “happiness.” Most of my time, however, was spent with kids in schools.

ALL TOGETHER In Kakuma, it is common for students of many ages to learn together in a single classroom.

RODGER BOSCH FOR UNICEF USAIn the Classroom

It’s midmorning at Mogadishu Primary School. Children in blue-and-white-checked uniforms crowd a dirt courtyard ringed by classrooms and shade trees. A girl drags a red loop of fabric strips linked by knots, used in a rope-jumping game. Little kids sip porridge

porridge

SEAN JUSTICE/GETTY

a soft food made by cooking grains in milk or water until thick

(noun)

Darryl likes to eat porridge for breakfast.

from red plastic mugs while a worker stands over a crackling fire and a bubbling pot of beans and maize

maize

SEAN JUSTICE/GETTY

a soft food made by cooking grains in milk or water until thick

(noun)

Darryl likes to eat porridge for breakfast.

from red plastic mugs while a worker stands over a crackling fire and a bubbling pot of beans and maize

maize

THODSAPOL THONGDEEKHIEO—EYEEM/GETTY

corn

(noun)

We grow maize on our farm.

—githeri: lunch for Mogadishu’s 21 teachers.

THODSAPOL THONGDEEKHIEO—EYEEM/GETTY

corn

(noun)

We grow maize on our farm.

—githeri: lunch for Mogadishu’s 21 teachers.

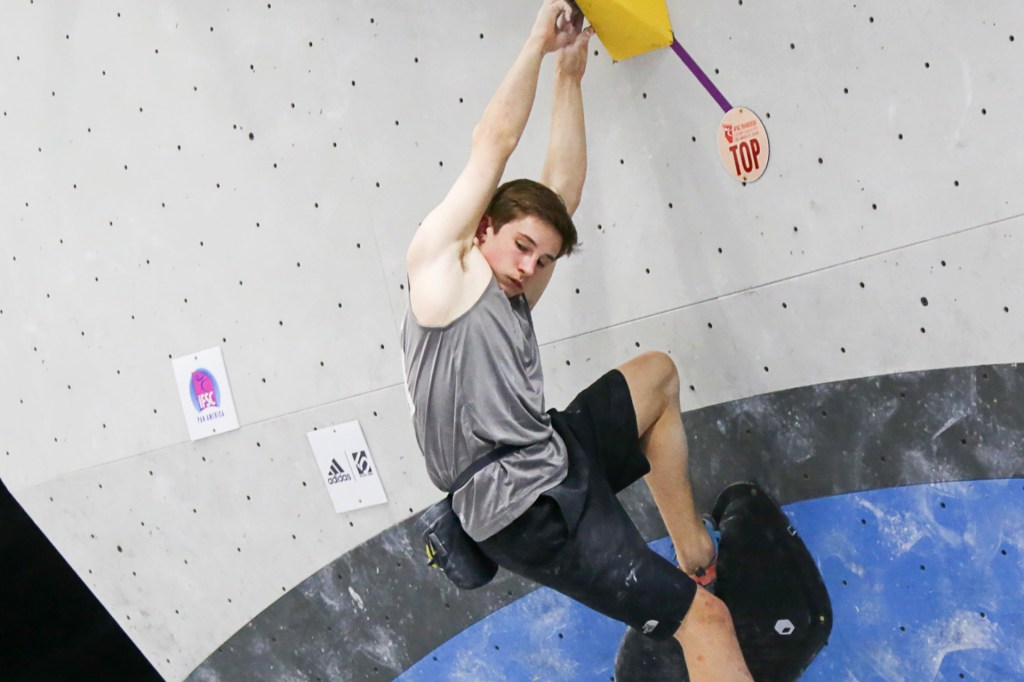

Head teacher Pascal Lukosi greets me in the office. “Enrollment is moving higher and higher, year after year,” he says. On this day, the school has 2,815 students. I quickly do the math: one teacher for every 134 students. Congestion is common in Kakuma schools. The average student-teacher ratio is 100 to one.

It’s also common in Kakuma to find students of many ages in a single classroom. Typically, primary school students are 6 to 13 years old. “[But] because of South Sudan being war-torn, they don’t go to school at the proper age” in their home country, Lukosi says. In 2017, Kakuma registered more than 23,000 new arrivals. “People keep coming,” Lukosi says. “They want to be in school.”

Motorbikes, called boda bodas, are the main form of transportation on Kakuma’s unpaved roads. But kids walk to school. There are no buses. For some, the trip takes more than an hour each way.

In the afternoon, I visit Bhar-El-Naam. Kakuma has 21 primary schools; this is one of two exclusively for girls. It’s around 4:00, and five students in uniform—purple dresses with wide white collars—cluster around a narrow wooden desk. I ask what they usually do after school.

ON ASSIGNMENT TFK’s Jaime Joyce talks with Rachel Akol Dau, 17, a refugee from South Sudan. “I want to be a journalist,” Rachel says.

RODGER BOSCH FOR UNICEF USA

EYES ON THE BOARD There are 21 primary schools at Kakuma refugee camp. Bhar-El-Naam, shown here, is one of two primary schools exclusively for girls.

RODGER BOSCH FOR UNICEF USA“I fetch water and wash utensils and clothes,” says Njema Nadai Ben, 12. The other girls nod in agreement. Homes do not have running water, so refugees walk to one of the camp’s 18 boreholes, or wells, to fill up.

What about homework? “We don’t have lights to read at night,” explains Rachel Akol Dau, 17. Homes also lack electricity. But Rachel and other students find a way to study. “I light firewood,” she says. “That gives me light.” She tells me, “I want to change the future of my family.”

EDUCATING GIRLS Jessica Deng, 21, was born and raised in Kakuma. Now she teaches math at Bhar-El-Naam.

JAIME JOYCE FOR TIME FOR KIDSJessica Deng, 21, teaches math at Bhar-El-Naam. She is also a former student here, having been born and raised in Kakuma. “Nothing is simple in this camp,” she says. Especially for girls. “[Some] are told ‘Don’t go to school.’ Others are told, ‘Do this [chore] before you go to school.’” And yet, “They come to school,” Deng says. “They’re so enthusiastic.”

Toward the Future

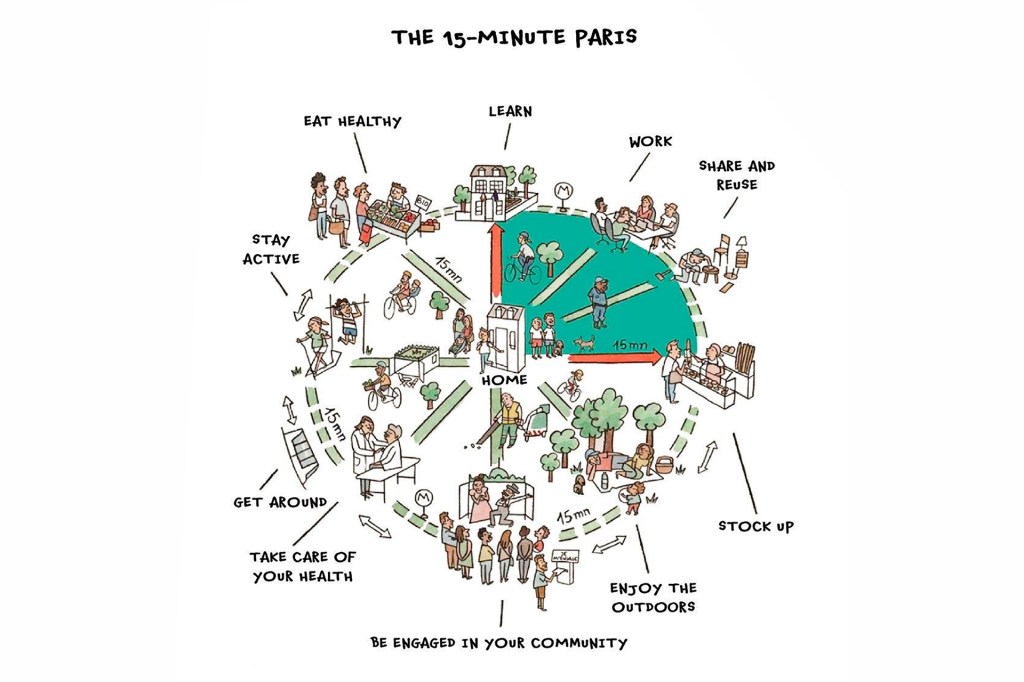

Established in 1992, Kakuma camp covers six square miles in remote northwestern Kenya. (See map.) Kalobeyei settlement opened nearby in 2016 to relieve overcrowding. Together, they’re home to nearly 186,000 people from 19 countries, including South Sudan, Somalia, and Ethiopia. Almost 60% are children.

Mohamud Hure is a U.N. education officer in Kakuma. “Refugees consider education to be a high priority,” he says. “But the education infrastructure

infrastructure

BRETT BEYER/GETTY

the basic equipment and structures that an organization or region needs to function properly

(noun)

The infrastructure of the United States includes more than 600,000 bridges.

is very limited.”

BRETT BEYER/GETTY

the basic equipment and structures that an organization or region needs to function properly

(noun)

The infrastructure of the United States includes more than 600,000 bridges.

is very limited.”

At Kalobeyei Friends School, 37 teachers and nearly 6,000 learners cram shoulder to shoulder in temporary classrooms built of sheet metal and wire. “We are just sitting on dirt” on a mat, student Jonathan Kalo Ndoyan, 17, tells me. “When the rains come, we have no place to sit.”

Materials are in short supply. At Kalobeyei Friends, 18 students share one textbook. Kenyan education standards say students should each have their own. But that’s not reality, says aid worker Kapis Odongo Okeja. “Standards are wishes,” he says.

TAKE A DRINK Children at Kalobeyei Friends School take a water break. The school’s 5,815 students meet in makeshift classrooms and sit on mats spread on dirt floors.

JAIME JOYCE FOR TIME FOR KIDSLast year, 8,000 students graduated from Kakuma and Kalobeyei primary schools. Only about 6% go on to secondary schools. There are just six of these—not enough to accommodate students who wish to continue their education for another four years. For now, students attend school in shifts. And for the first time, they’ve been asked to pay an annual $30 fee. While I was in Kakuma, a protest against the fee turned violent. Some schools shut down temporarily.

Morneau Shepell Secondary School for Girls was unaffected. That’s because a large corporate

corporate

ALEXANDER SPATARI/GETTY

related to a large business or organization

(adjective)

The company's corporate headquarters are located in New York City.

donor funds the boarding school. Here, 352 students have 17 teachers, individual desks, and Internet access. They wake at 4:30, eat breakfast at 6:oo, and start class at 7:30. “The school is there to give [the girls] a safe haven

haven

ALEXANDER SPATARI/GETTY

related to a large business or organization

(adjective)

The company's corporate headquarters are located in New York City.

donor funds the boarding school. Here, 352 students have 17 teachers, individual desks, and Internet access. They wake at 4:30, eat breakfast at 6:oo, and start class at 7:30. “The school is there to give [the girls] a safe haven

haven

SEBASTIAN ARNING—EYEEM/GETTY

a safe place

(noun)

The national park is a safe haven for deer, because hunting is illegal there.

,” says Mohamud Hure.

SEBASTIAN ARNING—EYEEM/GETTY

a safe place

(noun)

The national park is a safe haven for deer, because hunting is illegal there.

,” says Mohamud Hure.

HOMEMADE FUN A child holds a clay toy.

JAIME JOYCE FOR TIME FOR KIDSIn one classroom, students announce to visitors what they want to do in life. Doctor, lawyer, engineer, teacher, and pilot are popular professions.

Nawadhir Nasradin, 16, aspires to be a poet. After the bell rings, she recites

recite

HILL STREET STUDIOS/GETTY

to repeat from memory or read out loud for an audience

(verb)

Every morning, my class recites the pledge of allegiance.

one of her works. It ends with these words: “Education empowers.”

HILL STREET STUDIOS/GETTY

to repeat from memory or read out loud for an audience

(verb)

Every morning, my class recites the pledge of allegiance.

one of her works. It ends with these words: “Education empowers.”

It is my last day in Kakuma. I picture Rose, the girl I met on my first day. She dreams of returning to a peaceful South Sudan and of a career as a pediatrician. This year, she’ll take the Kenyan national exam required to graduate from primary school. I asked which school she attends. It’s called Hope.

How You Can Help

Of the world’s nearly 22.5 million refugees, more than half are under the age of 18. UNICEF works to protect children’s rights, including access to education.

UNICEF education kits (pictured, above, in use at Kalobeyei Friends School, in Kenya) are one way to do this. They contain basic school supplies, including books, pencils, scissors, and wooden blocks for counting.

“Whenever they come in contact with these kits, they are very happy,” says Songot Paul, head teacher of Kalobeyei Friends School. “They are motivated to learn even more.”

Would you like to help refugee students? Go to unicefusa.org/tfk to donate. A little can go a long way: $14 is enough for a set of 40 notebooks, 40 slates, and 80 pencils. You can also help by taking part in UNICEF’s Kid Power program. Visit unicefkidpower.org.

Jaime Joyce is executive editor at TIME for Kids. She traveled to Kenya to report this story. It is made possible through a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Correction: The original version of this story identified UNICEF as the United Nations agency that picked up Rose Peter at the Kenyan border. Such pick-ups are typically done by UNHCR, the UN refugee agency.

Assessment: Click here for a printable quiz. Teacher subscribers can find the answer key in this week's Teacher's Guide.